The Role of Prediction

Published:

Is machine learning the answer to creating flexible, capable machines? Can learning alone solve complex tasks? Perhaps, but, more likely, creating intelligent machines will require a certain degree of design, which we can think of as an architectural prior. In other words, a learning system requires a scaffolding on which to build. There is no better example of this than the intricate evolutionary structures of the human brain. This is the type of system we are striving for: hard coded low-level functionalities with a specific, yet incredibly flexible, higher-level architecture, resulting in the potential to quickly learn a large variety of tasks, i.e. general intelligence. Such a system walks the line between nature and nurture, trading off between pre-specified design and learning.

I feel the shortest path to creating intelligent machines is by modeling them after biological intelligence. And while the detailed mechanisms of biological intelligence remain largely unknown, there are computational theories and architectural constraints that should be given further consideration by the machine learning community. The most prominent of these, which I will discuss, is the role of prediction.

prediction is ubiquitous in intelligent biological systems

As we have developed improved tools to study and record from nervous systems, a growing body of evidence points toward the essential role that prediction plays in information processing within biological organisms. Predictive signals have been observed in visual processing [1], auditory processing [2, 3], hippocampus [4], motor cortex [5], and frontal cortex [6], and many other areas. Even the well-known phenomenon of spike-timing-dependent plasticity (STDP), which strengthens synapses that lead to post-synaptic firing, can by interpreted as a form of predictive learning. In our daily lives, a salient example of prediction is that split-second of shock when you go for that last step at the top of the stairs, only to find that it isn’t there. While our understanding is still far from complete, the theme of prediction appearing across organisms and brain areas seems to suggest a common strategy by which intelligent biological entities operate within their environments.

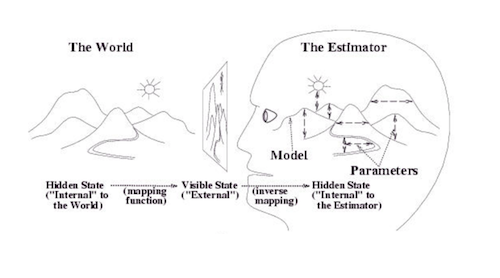

These observations and others have prompted various incarnations of what has come to be called predictive coding. This line of thinking dates back to 1860 with the German physicist and physician Hermann von Helmholtz [7]. After over a century and a half of inspired works (see [8] for a review), the core idea remains: intelligent biological systems construct probabilistic generative models of their surrounding environments. In other words, we do not passively observe the world (and ourselves). Rather, we maintain an internal model that actively predicts how events will unfold. When disagreement arises between the external environment and the internal model–the missed step at the top of the stairs–prediction errors act to update the internal model. The main implication of this theory is at once surprising and unsurprising: we each construct our own version of reality. This general scheme could underlie a range of cognitive functions, from perception to action and planning. The cartoon below, taken from [9], illustrates the perception component.

Predictive coding is also no longer purely a biological curiosity. The last two decades have seen continued progress by those within the neuroscience community in formulating mathematical models of predictive coding, with ties to Kalman filtering [9], variational inference [10], and reinforcement learning [11]. Likewise, the machine learning community has developed models in this direction, from the Helmholtz machine [12] to the more recent variational auto-encoder (VAE) [13, 14]. Nearly unbeknownst to the separate constituents, the similarities between these fields are becoming more pronounced. As the lines between these communities intersect, the exchange of ideas will hopefully foster further progress. The predictive coding community offers new ideas on modeling dynamics and action, whereas the machine learning community offers the ability to actually learn these models from large-scale, real-world data sets. The result could be another step in the path toward machine general intelligence as well as a better understanding of the computational underpinnings of biological intelligence.

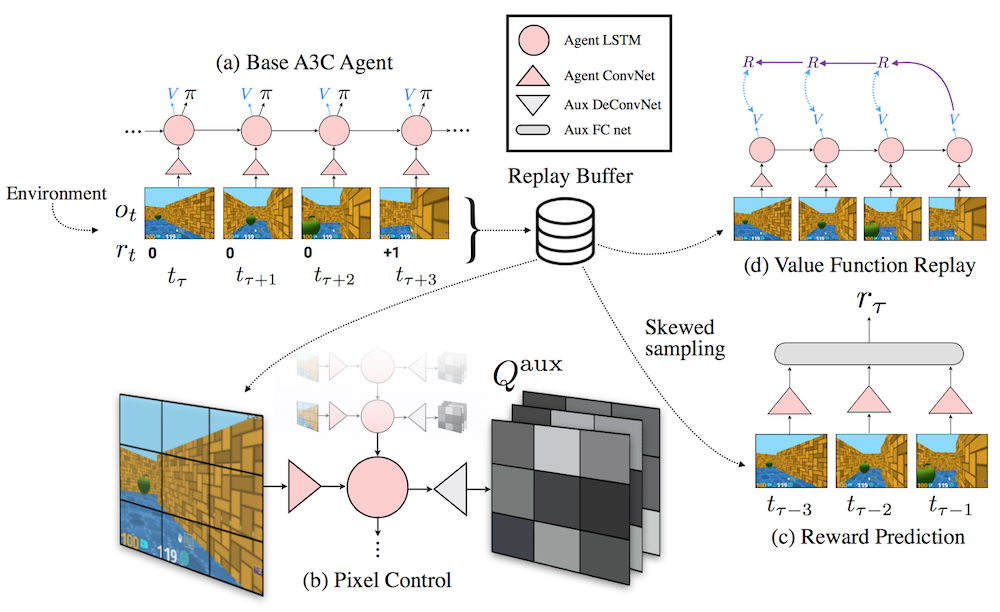

We are already starting to see examples where predictive approaches are yielding improvements in machine learning. A prime example is DeepMind’s UNREAL agent [15], which navigates virtual 3D environments while predicting aspects of its sensorimotor input and reward signal (see figure below). Adding these prediction tasks to the baseline reinforcement learning model allows the agent to reach higher performance on tasks much more quickly. This gets at the beauty of prediction, and generative modeling more generally; predicting the input provides a free learning signal. The learned representations can then be transferred to relevant tasks. When we eventually reach the point where we have highly capable machines that must interact in complex real-world environments, this, I feel, is the only sustainable approach for learning.

Current work in machine learning is still heavily reliant on supervised learning and reinforcement learning. The success of these areas has been bolstered by their clearly defined objectives, either matching the label distribution or maximizing reward. This allows the community to get behind a particular task or set of tasks and chip away at improving performance. Unsupervised methods, such as generative models, on the other hand, lack this benefit. Predicting inputs, in and of itself, is not a real task. And, therefore, by the definition given above, a purely predictive black-box agent is not intelligent, or at least it cannot be determined to be intelligent. Rather, the strength of generative modeling is in supporting supervised and reinforcement learning, particularly in environments where labels are not clearly defined or the reward structure is sparse or difficult to define. If we hope to achieve machine general intelligence, it will be through combining internal generative models with these other forms of learning, ideally on top of a rich sensorimotor input stream, all in the hopes of solving more difficult tasks.

Rao R, Ballard D. (1999). Predictive coding in the visual cortex: a functional interpretation of some extra- classical receptive-field effects.

Smith E, Lewicki M. (2006). Efficient auditory coding.

Wacongne C, Labyt E, van Wassenhove V, Bekinschtein T, Naccache L, Dehaene S. (2011). Evidence for a hierarchy of predictions and prediction errors in human cortex.

Mehta M. (2001). Neuronal dynamics of predictive coding.

Shipp S, Adams R, Friston K. (2013). Reflections on agranular architecture: predictive coding in the motor cortex.

Summerfield C, Egner T, Greene M, Koechlin E, Mangels J, Hirsch J. (2006). Predictive codes for forthcoming per- ception in the frontal cortex.

Helmholtz H. (1860). Handbuch der physiologischen optik.

Clark A. (2013). Whatever next? Predictive brains, situated agents, and the future of cognitive science.

Rao R, Ballard D. (1997). A Kalman Filter Model of the Visual Cortex.

Friston K. (2005). A theory of cortical responses.

Friston K, FitzGerald T, Rigoli F, Schwartenbeck P, Pezzulo G. (2017). Active Inference: A Process Theory.

Dayan P, Hinton G, Neal R, Zemel R. (1995). The Helmholtz machine.

Kingma D, Welling M. (2013). Auto-Encoding Variational Bayes.

Rezende D, Mohamed S, Wierstra D. (2014). Stochastic Backpropagation and Approximate Inference in Deep Generative Models.

Jaderberg M, Mnih V, Czarnecki W, Schaul T, Leibo J, Silver D, Kavukcuoglu K. (2016). Reinforcement learning with unsupervised auxiliary tasks.